Introduction

Sclerosing stromal tumour (SST) is a rare benign ovarian neoplasm of the sex-cord stromal category with distinctive clinical and pathologic features.1 It was first reported and named by Chalvardjian et al in 1973.2 Approximately 150 ovarian SSTs have been documented in the literature to date.3

The incidence of SST in ovarian stromal tumours is about 2% to 6%. Young females, in their second and third decades, are more susceptible to it. They commonly present with menstrual irregularities and pelvic or abdominal pain.1, 4

Histologically, SST is characterized by cellular heterogeneity, hemangiopericytoma like vascular structures, and a pseudo lobular architecture with cellular nodules separated by hypocellular, oedematous, and collagenous stroma.1, 4

On immunohistochemistry, stromal origin of SST can be demonstrated by the positive uptake of cells of SST to stains like vimentin, SMA and inhibin. SST cells do not stain for epithelial markers and S-100, and may or may not stain for calretinin or desmin. Stains like inhibin and calretinin are widely used for distinction of SST, from thecoma and fibroma.1, 2, 4

Because of the rarity of this neoplasm, only a few cases of SST have been reported in the literature. Herein, we report a case of SST of the right ovary in a 39-year-old lady.

Case History

A 39-year-old mother presented to OPD with complaints of prolonged menstrual bleeding for 2 years. Medical and family history were unremarkable. On, physical examination, the abdomen was soft and flat, without any palpable abnormalities.

Ultrasound of the pelvis, revealed a well encapsulated, oval-shaped, smoothly marginated enhancing solid cystic lesion, from the right ovary. Left ovary, uterus and endometrium were normal. Laboratory investigations were within normal limits. She then underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with right salpingo-oopherectomy and left salpingectomy.

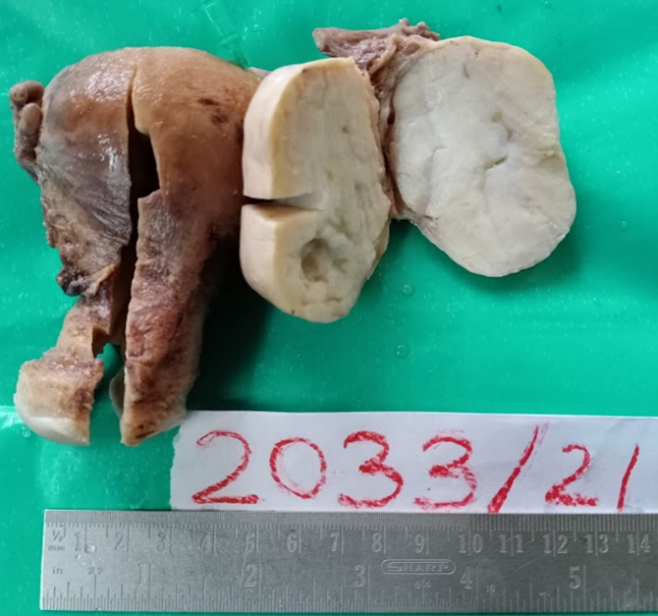

Gross examination showed a right ovarian mass, measuring 6x5x3cm, having a smooth and intact external surface. Inside, the cut surface was greyish-white to yellowish, solid, with a rubbery consistency and small cystic spaces (Figure 1). No Haemorrhage or necrosis was noted.

Immunohistochemistry(IHC) was not done as the patient had financial constraints.

Figure 1

Photograph of the right ovarian mass with grey-white to yellowish, solid cut surface with focal cystic spaces

On microscopic examination, sections from the right ovary showed a well-circumscribed neoplasm composed of cells arranged as lobules embedded in a hypocellular oedematous stroma(Figure 2), showing extensive areas of hyalinisation and numerous thin-walled branching hemangiopericytomatous vascular channels(Figure 3).

Neoplastic cells were predominantly epithelioid and focally showed spindle cell morphology(Figure 4). The epithelioid cells had pale eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm with central monomorphic round/ oval nuclei. Occasional cells with signet ring cell morphology were also noted (Figure 5).

The clinical and histopathological findings, lead to a diagnosis of SST.

Postoperative period was uneventful and she is scheduled for a follow-up pelvic ultrasonography after 1 year, to rule out any recurrence of the tumour.

Discussion

Ovarian tumours can be separated into 4 groups according to histological types.2 These groups include epithelial tumours, germ cell tumours, sex cord-stromal tumour. Among these, sex cord-stromal tumours are relatively rare and include about 8% of primary neoplasms. Various types of sex cord-stromal tumours include granulosa cell tumours, fibrothecomas, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumours, steroid cell tumours, and SSTs. Of these, SSTs account to 6% of all sex cord-stromal tumours.5, 6

Sex-cord stromal tumours, usually occur in the fifth or sixth decades of life, however, SSTs, usually present in the second and third decades of life. Presenting complaints are not constant among cases, but patients usually have menstrual irregularities, a palpable abdominal mass and pelvic pain. These features, alongwith the imaging findings for SSTs, can resemble those of borderline or malignant ovarian tumours. This therefore, creates a diagnostic challenge for proper care and treatment for the patient.

Most SSTs are hormonally inactive. It was initially reported as a non-functional benign ovarian tumour. Few studies suggest that SST cells can produce steroid hormones, which usually increase patients’ oestrogen levels, causing irregular menstruation, amenorrhea, and infertility. The youngest patient reported is a 7-month-old infant presenting with vaginal bleeding due to hypoestrogenism caused by SST. SST can also produce androgens, and many of these cases are usually reported during pregnancy.2

Our patient was a 39-year-old female who presented with prolonged menstrual bleeding. Just as in our case, there has been an increase in the number of SST cases, with menstrual irregularities being the most common symptom.1, 4, 7, 8 SSTs are predominantly unilateral and the right ovary is more susceptible than the left (around 71%).1, 4, 7, 8 Similarly, in our case, the patient had a tumour measuring 6x5x3cm in the right ovary. Contrary to that, Xi Zhang et al. documented a unilateral left ovarian mass in his case report.

Histologically, there is a characteristic pseudo-lobular arrangement, with cellular and hypocellular interlobular areas. Cellular areas have a dual population of cells made up of spindled fibroblastic cells and round to oval to polygonal lipid-containing cells. Some cells exhibit signet ring cell morphology. These cases are identified from Krukenberg tumours, as Krukenberg tumours are bilateral, seen in older population and show significant cytological atypia. Cellular areas with the typical vasculature may mimic vascular lesions, where inhibin can suggest the diagnosis of SST.

Patients with massive ovarian oedema might not have SSTs in their differential diagnosis. This can be confirmed by finding the entrapped ovarian tissue in the oedematous stroma.

At present, most scholars believe that SST originates from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells with multiple differentiation potentials in the ovarian cortex and can differentiate into smooth muscle. Immunohistochemistry and ultrastructural observation by electron microscopy favour this concept.2, 9

All of the ovarian SSTs reported in the literature were benign and were treated successfully by ovarian cystectomy or unilateral ovariotomy.1

Conclusion

Preoperative diagnosis of SST based on clinical and sonographic findings, is a major challenge, due to the rarity and overlapping features with malignant ovarian tumours. A possible approach would be to consider SST in differential diagnosis of young females with unilateral, complex, solid cystic ovarian masses, with related symptoms. As SSTs have a benign course, prognosis for these patients are relatively good, with conservative surgical treatment. Unique histopathological features helps to establish a definitive diagnosis.