Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic inflammatory and neurotropic disease caused by acid fast bacilli, Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae) and generally affects skin and peripheral nerves; however, other organ systems may also be affected. According to the National Leprosy Elimination Programme (NLEP) progress report for the year 2014-15, there has been a drastic decrease in the prevalence rate of leprosy in India.1, 2

It is well-known that histopathological examination of skin biopsy is important in the diagnosis of leprosy.3 The infection is often first evidenced in peripheral nervous system and the bacilli probably enter the nerves via endoneural blood vessels, which ultimately target the Schwann cells.4, 5 Therefore, nerve injury is a key aspect in the pathogenesis of leprosy.

In patients with early leprosy of both tuberculoid and lepromatous type, the abnormalities in nerve conduction studies and a histological picture of small fibre loss, with segmental demyelination and remyelination has been demonstrated. An impairment of cutaneous nerve fibres due to inflammatory reactions serves as a distinguishing feature for the diagnosis of leprosy from other cutaneous granulomas. Routine histopathological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stains cannot always determine the nerve twigs within a granuloma; whereas, S-100 immunostain, an immunohistochemical marker of Schwann cells, can be used to delineate the nerve involvement in tuberculoid leprosy.6

Several studies have evaluated the use of S-100 as an auxiliary diagnostic marker of leprosy.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 This paper reports the results of a study which investigated the use of S-100 for the early diagnosis of tuberculoid and borderline tuberculoid leprosy and compared the sensitivity of H and E stain with S-100 immunostain in discerning the nerve involvement.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive, prospective and retrospective analytical study was conducted at the Department of Pathology in a tertiary care centre over a period of 4 years. The skin biopsies of all histopathological cases of tuberculoid (TL) and borderline tuberculoid (BTL) were included in the study. Skin biopsies of all cases of lepromatous leprosy and those in type 1 and 2 reactions were excluded from the study.

All cases with the tuberculoid spectrum of leprosy were included in the study after retrieving appropriate clinical details from both retrospective as well as prospective cases. Based on a careful histopathological diagnosis, cases were diagnosed as TL or BTL.

A 3 to 5 mm punch biopsies of the representative skin lesion of the patients were received and stored in 10% formalin for histopathological examination. Further, the blocks which were prepared from these skin biopsies were utilized for performing immunohistochemistry using S-100 antibody.

Deparaffinized sections of the received tissue specimens were stained with HE stain and Fite-Faraco. HE stained slides gave the information about the histopathology of the skin lesion whereas Fite-Faraco stain helped to ensure the presence of Mycobacterium leprae, which are acid-fast organisms.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 3-4 µm thick sections of the blocks using antibody to S-100 (Novacastra, Mouse Monoclonal Antibody: P53-DO7-R-7-CE, RE7290-CE) after heat antigen retrieval.

Both HE slides and S-100 stained slides were examined independently and were studied for the patterns of nerve involvement. Sensitivities of HE and S-100 stains in identifying nerve involvement were calculated.

All data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22. The qualitative data were expressed as number (percentage) and the quantitative data were expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]). Chi-square test was used for assessing the sensitivity through comparative analysis.

Results

Out of the total 148 skin biopsies from patients with leprosy received in the department during the study period, 58 cases in tuberculoid pool were studied. Of these 58 cases, 28 cases (48.3%) showed features of tuberculoid leprosy and 30 cases (51.7%) showed features of borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

As shown in Table 1, 34 (58.3%) patients were females, the mean (SD) age at presentation was 43 ± 16.8 years and the age ranged from 14 years to 81 years. The majority of cases were seen in fifth decade of life followed by fourth decade of life, with a female preponderance.

Table 2 shows the distribution of clinical features among these cases. The majority of cases had range of several clinical features likehypopigmented patches (n=40), loss of sensation (n=36), erythematous patches (n=18), thickened nerves (n=35), visible deformities (n=1) and painless ulcers/ wounds or burns over the affected area (n=1).

The histopathological features of the skin biopsies were characterised by the presence of granulomas along the neurovascular bundles in both superficial and deep dermis. The granulomas were composed of epithelioid cells, lymphocytes and langhans type of giant cells. Epidermal changes were also noted.

Table 1

Age and sex distribution

Table 2

Distribution of observed clinical features across the study cases

Table 3

Distribution of casesaccording to histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis

Table 4

Comparison of sensitivity of HE staining versus S-100 immunostaining in delineated nerve fibres

|

Staining type |

Number of cases with delineated nerve fibres (%) |

Chi-square value (p-value) |

|

HE |

40 (68.9) |

6.48 (>0.05) |

|

S-100 |

58 (100) |

Out of the 28 cases of TL, 75% of the cases were found to have well-defined granulomas with increased lymphocytes placed around neurovascular bundles while remaining 25% had ill-defined granuloma formation. In the 30 cases of BTL, 50% cases showed well-defined granulomas with predominant epithelioid cells and frequent Langhans type of giant cells and 50% showed ill-defined granuloma formation.

The perineural infiltration was seen in all the study cases. There was destruction of nerves in 40 out of 58 cases. The nerve fibres were well delineated in 11 cases, partially delineated in 29 cases and the nerve destruction was not appreciated in 18 cases.

On careful histopathological assessment, out of the 28 cases of TL, 28% of cases showed well delineated nerve fibres, 57.1% of cases presented partially delineated nerve fibres and remaining 17.9% cases did not show delineation of nerve fibres. Further, in BTL cases, 43.3% of cases showed partially delineated and 13.4% of cases were seen to have well delineated nerve fibres. However, in remaining 13 cases (43.3%) the nerve fibres could not be delineated.

Most of the study cases (75%) showed unremarkable epidermis with few of them showing thinned out epidermis. Other epidermal changes which were noted include mild orthokeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis and focal exocytosis of lymphocytes.

Fite-Faraco staining was done in all the study cases to check for the presence of acid-fast bacilli. A total of four cases (6.9%) showed presence of lepra bacilli, which were from BTL group.

On S-100 immunoperoxidase staining the nerve involvement was described under 4 patterns: Infiltrated, Fragmented, Absent and Intact.

Figure 1

a: Tuberculoid leprosy; Photomicrograph showing well-defined epithelioid cell granulomas (H and E, x40); b: Borderline Tuberculoid Leprosy; Photomicrograph showing well-defined granuloma with Langhans giant cell (H and E, x400); c: Photomicrograph showing perineural lymphocytic infiltration (H and E, x100); d: Photomicrograph showing thinned out epidermis (H and E, x200)

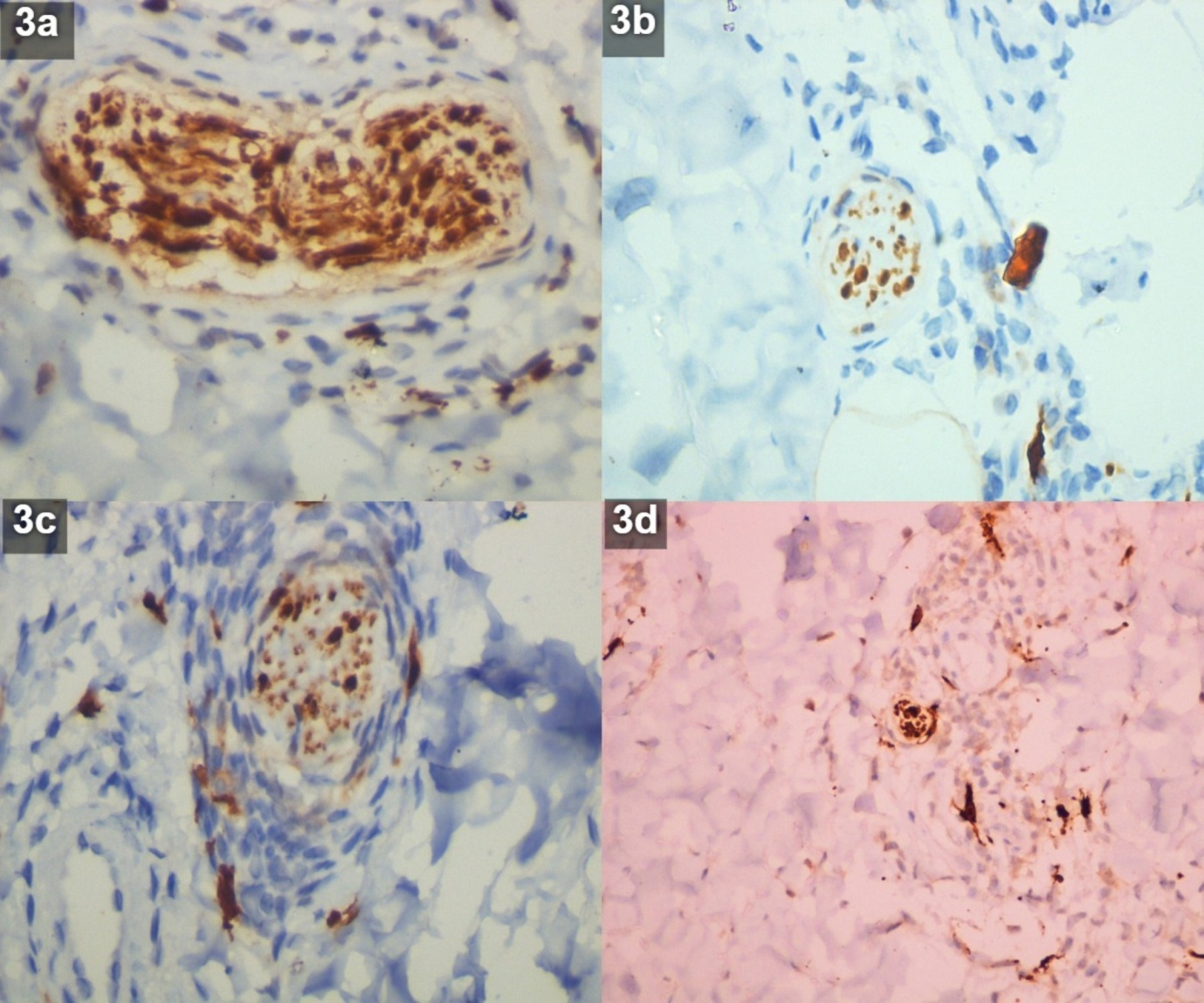

Figure 3

a: Photomicrograph demonstrating Infiltrated pattern of nerve involvement (S-100 IHC, x400); b: Photomicrograph demonstrating Fragmented pattern of nerve involvement (S-100 IHC, x400); c: Photomicrograph demonstrating Infiltrated and Fragmented pattern of nerve involvement (S-100IHC, x400); d: Photomicrograph demonstrating intact pattern of nerve involvement (S-100 IHC, x400)

Infiltrated

Identified as dark staining, fibrillar structures arranged in a wavy pattern with surrounding inflammatory cells. This pattern indicates that there is infiltration of perineurium by lymphocytes around the recognizable nerve fibre.

Fragmented

Identified as small, dark staining structures within granuloma which are identified as nerve fragments because of their fibrillar and wavy appearance though no intact nerve could be visualized. This pattern indicates a more advanced stage of nerve destruction.

Absent

No dark staining fibrillar structures within or outside the granuloma. This pattern indicates that there is complete destruction of nerves beyond recognition.

Intact

Dark staining, large fibrillar structures in a wavy pattern with no inflammatory cells inside. This pattern ruled out tuberculoid leprosy.

Fragmented pattern of nerve involvement was observed in 15 cases of TL (53.6%) and 17 cases of BTL (56.7%). Infiltrated pattern was seen in seven cases of TL (25%) and three cases of BTL (10%). Further, five cases of TL (17.8%) and nine cases of BTL (30%) showed both infiltrated and fragmented pattern of nerve involvement. Only one case of TL (3.6%) showed intact and both infiltrated and fragmented pattern of nerve involvement. And one case of BTL (3.3%) showed both absent and fragmented pattern of nerve involvement. Table 3 summarises the histopathological, histochemical and immunohistochemical findings of TL and BTL cases.

In comparative analysis, S-100 was found to be more sensitive (100%) in delineating the nerve fibres than HE stains (68.96%) (Table 4).

Discussion

Although the incidence of leprosy is decreasing, the expertise and the accuracy to diagnose leprosy have gained importance. Routine histopathological examination using HE staining may not identify nerve damage in all leprosy cases; however, for early and confirmatory diagnosis, recognizing the active destruction of cutaneous nerves by granulomatous inflammation in a skin biopsy is crucial. S-100 immunostaining method is effective in staining Schwann cells and in identifying nerve involvement in tuberculoid spectrum of leprosy cases. Thus, for confirmatory diagnosis of nerve damage, S-100 immunostaining can act as an adjuvant to histopathological examination of skin biopsies in all leprosy cases.

Patients presented in the age group of 14 to 81 years with majority in the age group of 4th to 5th decade. Our patients were slightly older by a decade when compared to other studies where the predominant age group of the patients presented was in 3rd decade.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Admitting to most of the studies, there was a male preponderance in the presentation of TL and IL whereas the present study showed a female preponderance with male to female ratio of 0.7:1, which was contradictory to other studies.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

In the majority of the study population, clinical observations have demonstrated the presence of hypopigmented patches with loss of sensation followed by erythematous patches. Several literature studies have displayed presence of hypopigmented patches as the predominant finding, a classical presentation of tuberculoid spectrum of the disease which was characteristically found in our study too.15, 18, 19, 23

In the present study, results of histopathological examinations revealed presence of granulomas along the neurovascular bundles, perineural lymphocytic infiltration and presence of Langhans type of giant cells. Further, epidermal changes were also noted in a few.

Well-formed epithelioid cell granulomas were observed in many studies along neurovascular bundles in the past. The present study also showed well-formed granulomas in 75% of cases of TL and are in concordance with the results of the study done by Bijjarigi S, et al. which demonstrated the presence of well-formed granulomas in 100% cases of TL.21 The other cases however showed more of a dense lymphocytic infiltration with few epithelioid cells around neurovascular bundles. In BTL group, we observed well-formed granulomas in 50% of cases and these observations are similar to the results of several past studies which showed well-formed granulomas in 45–75% of cases.15, 17, 19 The rest of the cases showed ill-formed granulomas with presence of langhans type of giant cells. Further, histopathological findings of IL patients from our study showed absence of well-formed epithelioid cell granulomas and a conspicuous dense perineural lymphocytic infiltrate which correlates with other studies.15, 17, 19 Therefore, these histopathological findings may aid in establishing the view that TL cases have better cell mediated immunity (CMI) than BTL cases.

In our study, epidermal changes were variable from unremarkable to atrophic. We found thinned out epidermis in 4 cases of TL and unremarkable epidermis in 19 cases of TL. These findings are parallel with the observations of the study done by Bijjarigi S, et al. who demonstrated thinned out epidermis in 2 TL cases and unremarkable epidermis in 20 TL cases.21 Moreover, BTL cases from our study showed thinned out epidermis in 2 cases and unremarkable epidermis in 24 cases and these results are in concordance with the results of study conducted by Badhan R, et al.17

By and large, the tuberculoid leprosy cases will not show positive acid-fast bacilli (AFB) under Fite-faraco staining. In TL, cell mediated immunity is strongly expressed and the bacillary multiplication is restricted to few sites and the bacilli are not readily found in the skin biopsies. AFB positivity will be displayed in lepromatous spectrum of cases as it represents the failure of cell mediated immunity with resultant bacillary multiplication, spread and accumulation of antigen in infected tissues. The present study showed positivity for fite-faraco in 6.9% (4/58) of cases in tuberculoid spectrum and all the 4 cases were BTL. This result is correlating with the results of other studies.14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 23, 24, 25

On immunohistochemical analysis using S-100 stain, we observed four different patterns of nerve damage: infiltrated, fragmented, absent, and intact. The present study showed fragmented pattern of nerve involvement in 53.6% of the cases of TL, infiltrated pattern in 25% of the cases and both infiltrated and fragmented in 17.8% of the cases. There were no cases which showed intact or absent pattern which correlates with other studies done by Thomas M, et al., 12 and Gupta SK, et al.10 This suggests the nerve damage in TL which correlated with perineural granulomatous infiltration on HE staining which connotes the ongoing destruction process. This also conveys that the disorganization and destruction of dermal nerves is a more consistent finding in the diagnosis of TL than the absence of nerves.

The present study demonstrates fragmented pattern of nerve involvement in most of the cases of BTL (56.7%) which is in concordance with several studies done by Gupta SK, et al.,10 Mohanraj A, et al.,11 and Thomas M, et al.12 Thirty percent of BTL showed both infiltrated and fragmented pattern which was predominant pattern observed in the study by Tirumalae R, et al.26 None of the BTL cases of the present study showed intact or absent pattern of nerve involvement whereas literature documents absent pattern in a proportion of cases.10, 11, 12, 26 The present study recognized absent and fragmented pattern of nerve involvement in 3.3% of BTL cases which is correlating with the cases reported by Mohanraj A, et al.11

In comparative analysis of the sensitivity of HE staining with S-100 immunostain in delineating the nerve involvement, we observed that the sensitivity of HE in delineating the nerve involvement is 68.3%. These result concords with the results of the study done by Tirumalae R, et al., who reported the sensitivity of 41%. Further, sensitivity and positive predictive value of S-100 in our study was found to be 100% which falls in the same line as the study results of Gupta SK, et al.,10 and Thomas M, et al.12 Thus, we can conclude that S-100 is more superior to HE in delineating the nerve involvement.

The results of the study demonstrate the advantage of S-100 immunohistochemical staining in the early and differential diagnosis of nerve damage in skin biopsies of leprosy. Use of S-100 immunostaining along with histopathological analysis will aid in accurate and confirmatory diagnosis of TL and BTL.